Patterned Utterance – Sarah Tremlett

View +- Magazine below for an article on Sarah Tremlett‘s microscopy poem Patterned Utterance.

Chance Operations, an essay on Bath Spa Fluxus prints at MIX 2012 -Sarah Tremlett

Chance Operations1

A conference is born with mysterious ancestors / sourcing the origins of the ‘Fluxus’ prints

Website introduction for the founding of MIX, Merging Intermedia conference, 2012, Bath Spa University2

By Bath Spa Creative Writing alumni Sarah Tremlett

Whilst visiting Berlin five years ago I bought a copy of Fluxus In Germany – A Long Tale with Many Knots (my husband acerbically commented that we couldn’t have flown Ryan Air, then, as we usually only take hand luggage, and the publication in question is the size of a healthy, pregnant, spiral- bound file). The book has a thick, corrugated-plastic, transparent cover (the kind of material normally used for packing), which, like a fog obscuring headlights on a November night, partly conceals a dim inner glow of mustard and maroon sheets, pleasingly delivering a seemingly inexhaustible supply of stentorious text. From time to time I have lovingly opened it and gazed at the curious goings-on – absorbed the muddied cartwheels of genius flung up from various associations and happenings, captured forever within the pages. However, in some senses it has been a bit of a tomb-like tome – part art-collectible object; one of those works which sit and wait on the shelf, pausing; somehow or another it hadn’t yet revealed its full potential or purpose – what was this ‘tale’ doing on my shelf, after all?

Over a year and a half ago, now, I happened to meet Lucy English at a poetry conference at Chichester University. We were both travelling back ‘on the train’ and, as normal for England on a Sunday, there weren’t any trains – not until somewhere in the middle of Wiltshire – so we spent a good deal of time on the bus together. Conferences became the topic of conversation – since (as some of you may well know) Lucy had run a particularly groovy poetry gathering at Bath Spa three years previously. Turning things over we ruminated and extrapolated about how Bath has much to offer and then it was time to get off. Time passed. In the spring of 2011 like the rising of a new tide, I felt it was time to get to grips with this now, fairly established genre of videopoetry, and got in touch with Lucy – what about a conference on video narratives? We began to hatch our plan and the big, glowing, plastic bound file began to vibrate. At the same time, unbeknownst to us, another slumbering giant was about to reawaken, deep in the corridors of the topiarised and be-peacocked Elizabethan manor – Corsham Court (which was originally Bath Academy of Art and now a home to Bath Spa University postgraduate research students). One stormy afternoon, with rain lashing at the mullioned windows, in the course of archiving old material a long-forgotten drawer was re-opened; it revealed two B2-sized plastic bags. Inside the transparent containers were three editions of assorted prints (ED.912 stamped on every sheet, and mostly dated around 1967) by Maciunas, Brecht, Diacono, Sassi and Blaine, alongside many others.

Parole in libertà, Eugenio Carmi, Ed. 912 Milan, 1967,

Parole in libertà, Eugenio Carmi, Ed. 912 Milan, 1967,

70 x 50 cm; Bath Spa University collection

The provenance of the prints, it transpired, was a complete mystery. However, they became variously known as ED.912 or the Fluxus prints (since one entitled US surpasses all Nazi genocide records was by the originator of the term Fluxus – the Lithuanian artist George Maciunas), and were believed to be part of the art collection which had been established by Clifford Ellis (the director from 1937-1972). They were thought to have left Corsham Court in 1986, when the art school moved to Sion Hill, in Bath. It is understood that the prints lay in the art school library at Somerset Place for around twenty years until the building was sold, at which point they were returned quietly and unobtrusively to their current location. Their peripatetic journey had ensured both their mystery and their survival – being in more or less pristine condition – but were they, like Tutankhamen’s tomb, cursed by their discovery – an enigmatic ‘tale with many knots’? Guess what! Lucy emailed. Serendipity I texted; the Fluxus spirit is alive and kicking! The conference began to materialise, seemingly shadowed by a coincidental ghost – but was it a coincidence?

Why were the prints at Corsham Court, and how did they get there in the first place? The mystery, (like many conundrums surrounding the itinerant people, places and origins of Fluxus, itself), gradually deepened. Rumours abounded. Some said the prints were collected by the artist John Furnival and used as examples during graphic design classes (drawing-pin holes on the corners), recalling the heady, hands-on, chiaroscuro days of moveable type, leading, set-squares (and yes, even the wormy detritus of messy rubbers) amidst the eccentric iconoclasm of Elizabethan bohemia.

Definitions and Consent

But were the prints actually examples of Fluxus work, or not? Like the term itself, (which can be defined as a term for an anti-term), this theory seemed perpetually under debate. Soon, the practicalities of life took precedence, and a happy state of ‘not knowing’ seemed the most appropriate way of moving forward. It was as if the chance discovery and the questionable provenance were part of the ‘event of the prints’; a performance which we were enacting, a sort of Fluxus motion, as if George (Maciunas) might have been looking over the progress of the conference and maybe, even, having a quiet chuckle.

As is well-known, Maciunas was no stranger to attempting to martial and classify groups of mercurial artists; according to sources (and please let us know if you have any information to add) he reportedly coined the term when he organised the first Fluxus event in New York in 1961. Dick Higgins, in his ‘Child’s History of Fluxus’ describes Maciunas as having chosen the name as a ‘very funny word for change’. It is well-known that the lineage of the often text-based Fluxus family tree of indeterminacy, chance and flow, is many-branched, and springs from many sources, such as George Brecht – though the ‘face’ to set all fonts scattering is nearly always cited as the legendary pioneer John Cage. Apparently, whilst not directly following Cage’s theories, Maciunas had a good knowledge of, and a ‘respectful affection’3 for, his earlier experimental music. Whether an artist saw themselves as part of Maciunas’ definition is another matter. Reflecting on this question, I notice that my Fluxus tome is beginning to glow once again, vibrating to the voice of Johannes Cladders in his reminiscences with Gabriele Knapstein (p.6):

I can no longer say with certainty whether I was familiar with the term at the time.

Knapstein goes on to add:

George Maciunas… understood how to bring artists from very different areas and approaches into actions together under the name Fluxus, but the artists only identified in part with the definitions that Maciunas tried to give the term during the early sixties… there were continual differences of opinion as to who would be allowed to lay claim to the term Fluxus and who wouldn’t.

He observes, however, that Maciunas found the term useful to suggest an opposition to:

art’s rigidification since the late fifties by reconnecting to the avant-garde movements of the 1910s and 1920s. In the face of the strong presence of abstract painting and sculpture in the postwar era, they pushed ahead with their interdisciplinary approaches to broaden the conception of art.

So, it seemed appropriate enough, for the moment at least, that we could consider the spectre of the prints surrounding the conference as a blessing of consent – yet their mystery remained unsolved. Time passed.

From stillness to motional text: Fluxus to video narrative and videopoetry – a family ‘videopoetree’?

It can be argued that many of the Fluxus worldwide ‘family’ of artists, belong to yet another species – the family of visual poets. We can even attempt to mark a rough ‘videopoetree’ – which, like ‘the word’, itself is both a linear, yet also three-dimensional, anthropocentric ‘body’, which, ultimately in alignment with technology, has discarded the white page for time and motion and photonic text.

As is commonly recognised, poetic writing which is ‘visual’ and straining to run free can be cited as far back as a few centuries BC, primarily with Hellenistic pattern poetry. Examples can be found throughout history, with or without religious reference, but for the moment we will launch our family tree at the end of the nineteenth century with Mallarme’s oft-mentioned Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (A Throw of the Dice Will Never Eliminate Chance) of 1897 (published in book form in 1914).

La Colombe Poignardée et le jet d’eau from Calligrammes: Poems of Peace and War,

La Colombe Poignardée et le jet d’eau from Calligrammes: Poems of Peace and War,

(1913-1916), Guillaume Apollinaire4

Moving on to Futurist manifestos 1912-14 – Marinetti’s use of Parole in Libertà (Words in Freedom) echoing and blasting to Zang Tumb Tumb alongside the visual pleasures of Apollinaire and his Calligrammes; stumbling on in decades through Eliot, Tristan Tzara, Hannah Höch and Gloria (Stein) – still the ultimate beginning for the majority of free-forming wordsmiths – although, not to forget, ever, the dash master – Virgina Woolf; to what I am calling the first two (Dadaist/Surrealist) examples of filmic poetry – Man Ray’s cinépoéme Emak-Bakia (Basque for ‘Leave me alone’), and Marcel Duchamp’s rotating text-based work Anemic Cinema (both from 1926).

Anemic Cinema, Marcel Duchamp, 1926

Anemic Cinema, Marcel Duchamp, 1926

We stay in Paris to mark the end of World War II, Lettrism (Letterism) and the highly significant Rumanian artist and theorist of music Isidore Isou, before moving on to happenstance, Brecht, Cage and Concrete Poetry (Brazil 1955/6), recognising artists such as Ben Vautier pre-Fluxing under the Nice sun, before the beginning of our world in 1959 with Gysin and Lutz in Stuttgart and what are generally considered to be the first programmed computer texts.

Theo Lutz in Stuttgart had already produced the very first electronic poetry, ‘stochastichte text’ in Augenblick… More than ten years later, the first exhibition of automatically produced poems took place in 1975 during the ‘Europalia’ event in Brussels.5

Back to Paris and Liliane Lijn (spinning cylinders with poetic words describing the physical properties of the universe – dissolving ‘symbols of vibrations’6), alongside Burroughs, Calvino, the Beat Poets and the ‘Séminaire de Littérature Expérimental’ (Experimental Seminar of Literature), which became known as ‘OULIPO’ (founded in 1960), to explore the new area of electronic poetry.

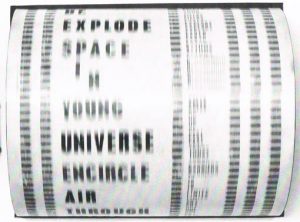

Young Universe, poem drum, Liliane Lijn, 1962

On with the worldwide spreading of Fluxus, through to Art and Language, L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry, conceptual art, mail art and a convergence of programmable, motional text and new thinking expanding across all disciplines. As Friedrich Block states in Kac’s Media Poetry – an International Anthology:

…the likeness between experimental poetics that developed since the 1950s and the philosophical reflection on language (e.g. Derrida’s ‘Grammatology’, 1967), the media revolution (e.g. McLuhan’s ‘The Gutenberg Galaxy’ 1962), and science (Heinz von Foerster’s and John von Neumann’s ‘Cybernetics’) stand out… Around 1967 and 1968 an intellectual climate emerged – at least in Europe – within the context of social, political and cultural movements, which set the stage for the contemporary discourse on digital poetry and media art (2007, p. 232).

Denomisegninatura, Mario Diacono, 1962

Denomisegninatura, Mario Diacono, 1962

And, with particular relevance to motional text Block goes on to state:

the development of experimental poetry as form or movement (my italics) must have been complete by the late 1960s (2007, p. 235).And, with particular relevance to motional text Block goes on to state:

Stopping for a while and contemplating with Dom Sylvester Houédard, John Furnival, Bob Cobbing (sound and vision), Marcel Broodthaers (looking back to Mallarmé), Franz Mon, Mario Diacono, Gianni Sassi (and all Fluxus-like in Milan), Dick Higgins (and all the artists in the prints) before heralding the broadcast in 1969, of what has been described (setting aside Man Ray’s and Duchamp’s filmic text) as the first videopoem – Roda Lume (Wheel Light) – by Ernesto de Melo e Castro (black and white 2 minutes, 50 seconds). Melo e Castro describes it as:

integrated verbal and non verbal signs, and theO som foi vocalmente improvisado pelo autor, constituindo um poema sonoro de ruídos e letras e palavras. sound was vocally improvised by the author, as a tone poem of sound, letters and words.7

As Ernesto de Melo e Castro stated:

The page is no longer there, not even as a metaphor. Space is now equivalent to time and writing is not a score but a virtual, dimensional reality…8

Roda Lume (Wheel of Light), Ernesto de Melo e Castro, videopoem, 1969

Roda Lume (Wheel of Light), Ernesto de Melo e Castro, videopoem, 1969

And now we are reaching up through Art and Philosophy and Joseph Kosuth, Nancy Spero’s broken voices of torture entombed with Antonin Artaud, and on to the end of the 1970s where the ‘truistic’ text-based prints of the artist Jenny Holzer, were soon to morph into world-encompassing motional, poetic digital texts.

The Watershed Moment

By 1985 the now seminal Les Immatériaux exhibition at the Pompidou Center in Paris was a turning point for the motional word. The videopoet Philippe Bootz called Les Immatériaux the ‘starting point of dynamic poetry’ (Kac, p. 214); stating that he himself began with generated texts in 1977 and only began working with meaningful or animated poetry in 1985. Bootz termed 1985 as a transitional period, but stated that all the elements were there at that point, with the first symposium taking place at Cerisy in that year.

Transmission Hologram (still), Richard Kostelanetz, 1987

Transmission Hologram (still), Richard Kostelanetz, 1987

It was in 1985 that Melo e Castro Entre 1985 e 1989, desenvolveu na Universidade Aberta de Lisboa um projeto de criação de videopoesia denominado SIGNAGENS. began the Signagens (Signings) videopoetry project at the Open University of Lisbon, where he pioneered the idea to use the character generator to produce animated poems, designed specifically for television.

Genesis, Eduardo Kac, video and biotechnological texts, 1999

Genesis, Eduardo Kac, video and biotechnological texts, 1999

Nesse projeto, Melo e Castro teve a idéia pioneira de lançar mão do gerador de caracteres para produzir poemas animados, pensados especificamente para veiculação na televisão. At the same time the insanely prolific Richard Kostelanetz was producing short video poems and fictions using Amiga text programs compiled in randomly accessed DVDS titled, Video Poems and Video Fictions; and on the other side of the pond in Italy, Gianni Toti (poet and writer) created ‘Poetronica’ a hybrid of poetry, cinema and electronic art.

The moving videopoem had arrived, along with George Aguilar, Caterina Davinio, Javier Robledo, Mark Amerika, Maria Mencia, Tom Konyves and the mould-breaking Eduardo Kac – bringing into being Biotechnological texts and genetically coded text – now the family chronopoetextree is literally ‘written in the genes’.

The Mystery Revisited

As in any list or family tree this is not meant to be a conclusive summing up, but simply a writerly pebble skimming the water of a wide and (literally) deep-flowing river of wordsmiths. But one ripple, one aspect of this ‘knotted tale’ is the rising to the surface of the enigmatic ‘Fluxus’ prints. Almost a year after the conference was first mooted, I found myself turning over the mystery, once again.

Le poème visuel III, Jirí Kolár, Ed. 912 Milan, 1963,

Le poème visuel III, Jirí Kolár, Ed. 912 Milan, 1963,

70 x 50 cm; Bath Spa University collection

I realised, that for my part, it was less a story about who had brought the prints to Bath Academy of Art, but why they were produced in the first place. I discovered that ED.912 and d.EDsign were a series of prints produced in Milan (around 1967) by Edizioni di Cultura Contemporanea, with a connection to BiT (the avant-garde Italian art magazine), edited by Daniela Palazzoli and co-edited by Germano Celant, Mario Diacono and Tommasso Trini. Many of you will recognise these stellar names as cultural leviathans on the current art world scene – not only attuned to any social seismic shift that might rupture into new art – but traversing history in such a way as to enable their visions to green-light trends and literally make movements.

I managed to contact the Italian artist Mario Diacono – who had created the print Appel – and I now include the extremely generous and generally heartbeat-skipping reply:

What you call prints were intended to be also posters, not in the sense of affiches though, but rather of something combining the aesthetic intent of the print with the unlimited production/diffusion of the poster. Ed. 912 was also the publisher of BiT9, but the poster- prints were, in fact, independent from the magazine. Celant, Trini, Palazzoli and I were editors of BiT; the posters were the brainchild of Daniela Palazzoli and of Gianni Sassi, the graphic designer (and an owner) of Ed. 912. They were the ones selecting the artists, writers, etc from whom the poster-prints were commissioned.

APPEL, Mario Diacono, Ed. 912 Milan, 1967,

APPEL, Mario Diacono, Ed. 912 Milan, 1967,

70 x 49.5 cm, Bath Spa University collection

(Regarding) the basis of what my intentions were in making the visual poem Appel/Apple, I recall, the pieces attempted to use the medium of typographic, design-like objects as a way of going beyond the print, the poster, the book, etcetera. It was an attempt, in a word, to socialize, to push in the direction of a diverse accessibility, the fruition of art and literature; to push them beyond their traditional field of creation and consumption. Probably the immediate inspiration for the poster-prints had been the work of the Fluxus group, but I was also thinking a lot about the graphic revolution of Schwitters, Futurism, Lissitzky, etc; while Daniela had very much in mind Marshall McLuhan.

So, as we look back to 1967, we see that Diacono looks back to Schwitters – the lineage loops back to draw in another thread. As if this news wasn’t enough, there was yet another weaver (or decoder) of the ‘knotted tale’ on the horizon – Daniela Palazzoli, herself:

What I can immediately tell you about the three sets of posters is that they were part of the cultural strategy of our publishing house: ED912. We were making books, a magazine titled BiT Arte oggi in Italia, and three or four lines of posters. Many of the issues you briefly introduce (anti-US propaganda/ anti-Vietnam, avant garde graphic design, Marshall McLuhan) inspired our thoughts at the time – also because many of the people you are quoting (Maciunas, Brecht, Sassi, Diacono) were friends of us – or at least of me, because I was spending much time in the US where I was also teaching at Rutgers University.

Fiat Lux, Till Neuberg, Ed. 912 Milan, 1967,

Fiat Lux, Till Neuberg, Ed. 912 Milan, 1967,

70 x 50 cm; Bath Spa University collection

Daniela continues:

We represented Fluxus in Italy, sharing with George Maciunas and the many, many people who collaborated with him all over the world that art had to extend in everyday real life, interacting and involving more people thanks to its ability to dialogue and be understood from individuals with different habits, cultures, and so on. Personally, I was also inspired by Marshall McLuhan intuitions – I was also a good friend of one of his co-authors, Quentin Fiore. For example, I made many shows about books conceived as artworks; and one in particular called ‘The Dragon teeth: The Transformations of the page and the Book in the post-Gutenberg age’ – was devoted to the passage of poetry, page and book from only a visual and intellectual to a total experience.

Through Diacono and Palazzoli the Fluxus posters had risen up like a Phoenix to ‘dialogue’ with videopoetry; as Palazzoli mentions herself:

the original principle to produce them being that these posters were a good extension of art, poetry and cultural revolution (as) messages (being sent) into young people’s intimate living spaces and personal rooms – they were very successful at the time.

Movimento, (repeating the word movimento), Arrigo Lora Totino,

Movimento, (repeating the word movimento), Arrigo Lora Totino,

Ed. 912 Milan, 1966. 70 x 50 cm; Bath Spa University collection

At last it was as if the prints – now posters – had spoken (not in the way that Cage complained about – the sound of the voice of the artist), but in the way of the city street – viral, vital, deafening; yet suddenly noticing something that had been there all the time. The Fluxus connection was alive and kicking – not with big statements, but incidental yet crucial thoughts to the remembered everyday tasks10 of the works. How appropriate to think of the similar efficacy of videopoetry – streaming as it does into anyone’s ‘intimate spaces’. Now it appears that a series of posters that were once surprise guests to the party have become its hosts.

As Ben Vautier ventures: ‘We can, in Fluxus, always find somebody who did it before;’11 that being the case, here lies a text lineage that, in part, presaged the videopoem and enabled its birth. These posters, as ‘inert’ or still works (of course dynamically possessing in perceptual terms multifarious directed and semantic tensions) provide part of the context – the gene pool – for moving visual poetry in the 21st century.

Telegram from Vietnam, Cavan McCarthy, Ed. 912 Milan, 1967,

Telegram from Vietnam, Cavan McCarthy, Ed. 912 Milan, 1967,

70 x 50 cm; Bath Spa University collection

Perhaps the Maciunas Fluxus Manifesto of 1963 might bear re-examination in the light of Tom Konyves’ Manifesto of Videopoetry, which we will be fortunate enough to share at MIX. From calligrammes to film poems, chance, cut-ups and biotext – as we survey this roll-call of pioneers (please forgive any omissions), how many similarities and differences can be further discussed and debated between visual texts and the current practice of videopoetry?

Has movement really changed the word for good? Whilst there is little denying that motional text (which in any case is also ‘still’ since it works on the perception principles of the Phi phenomenon12, like all filmic works), has introduced many new philosophical and theoretical concepts, maybe these posters have re-awoken at this moment in time for a particular reason. Maybe the Fluxus spirit of the 1960s is here to remind us that digital, motional text isn’t everything – as Cavan McCarthy’s poster reminds us, we, as individuals, with our ‘habits and cultures’ also have other things to discuss.

1 Term ‘Chance Operations’ in Block, René (ed.): Fluxus in Germany – A Long Tale with Many Knots 1962-1994 Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen, Stuttgart, 1995: in An Anthology – Jackson Mac Low and La Monte Young, New York, 1963 Full title: An anthology of chance operations concept art anti-art indeterminacy improvisation meaningless work natural disasters plans of action stories diagrams Music poetry essays dance constructions mathematics compositions (download: http://www.ubu.com/historical/young/index.html)

2 I co-founded MIX with Lucy English at Bath Spa University

3 Jean-Pierre Wilhelm, 1962, The Fluxus Reader, Ken Friedman, 1998, Academy Editions

4 http://writing.upenn.edu/library/Apollinaire_Calligrammes.html

5 French e-poetry – a short/long story by Patrick-Henri Burgaud www. Dichtung-digital.com 2002/05-25-Burgaud.htm

6 Catalogue interview with Charles Dreyfus for Lijn’s Koan exhibition in Paris, 1997

7 www.cibercultura.org.br/tikiwiki – The Encyclopedia of Technological Art

8 http://www.ociocriativo.com.br/guests/meloecastro/video.htm

9 An avant-garde, Milan-based art magazine.

10 Alison Knowles www.alisonknowles.com

11 www.Benvautier.com

12 The phi phenomenon is an optical illusion defined by Max Wertheimer in the Gestalt psychology in 1912, in which the persistence of vision formed a part of the base of the theory of the cinema, applied by Hugo Münsterberg in 1916. This optical illusion is based in the principle that the human eye is capable of perceiving movement from pieces of information, for example, a succession of images. In other words, from a slideshow of a group of frozen images at a certain speed of images per second, we are going to observe constant movement.

Tom Konyves – “Todos esos momentos”

Vidĕo: Todos esos momentos se perderan from Dier on Vimeo.

Dier videopoem Todos esos Momentos by Tom Konyves (click to read the article)

Dear Alison by Helen Mort

‘I Write to You Because Your Imprint’s Everywhere’

From the anthology No Map Could Show Them (Chatto & Windus, 2016) poet Helen Mort has focused on women who have had a particular relevance to her and across history. In ‘Dear Alison’ she writes not about but to the late Derbyshire-born mountaineer Alison Hargreaves who died climbing in 1995, and whose decision to continue climbing in the face of being a young mother has left its haunting shadow in her wake.

In discussing the making of ‘Dear Alison’ Helen observed how for her mountaineering and writing poetry are very similar; and how the act of climbing might help shape a line of poetry on the subject – an area that Judy Kendall herself is familiar with.

The resulting poetry film, made with Dark Sky Media and UKClimbing.com sits between a form of documentary tribute through poetry, and an evocation of the very themes that preoccupy the poet herself. It is in fact a form of portrait of Helen through Alison; or, not only Helen as conduit for Alison but Alison as conduit for Helen, where we see Helen more clearly as a result. And it is also a metanarrative on the process of writing: of the struggle of putting one word after another; of literally conceiving poetry, line by line.

The film follows Sheffield-born Helen as she climbs at Stanage Edge rising dramatically above stark moorlands in the Peak District, UK. She has mentioned before that this is a place where she finds she can compose; where lines surface and images resonate, whether climbing, running or walking with her whippet Charlie.

Echoing the contrast of the landscape the filmmakers have shot Helen’s authorial journey partly in extreme close-ups as if we are trying to see as close as possible into Helen’s mental poetic footholds, as well as the wider rock-climbing experience. As such the filmmaking is astoundingly direct, condensed and uncompromising; it is held together editorially as a series of complete visual vignettes, rather like the serial nature of climbing itself, from ledge to ledge. Most importantly we feel we are with Helen not watching her, and as such we also are touched by and reminded of Alison’s journey and spirit. Here the protagonist as writer but also climber is constantly shadowed by her subject, and as Helen moves up the rock face we sense both the struggle to write but also the struggles of women who are courageous and take risks.

With the topic of non-metaphorical poetry films still echoing in our minds we also might consider this particular work as riven with metaphorical seams (rock metaphors to discuss metaphor notwithstanding). Throughout ‘Dear Alison’ close-up shots of Helen’s hand writing the poem punctuate the film and at the end she draws a firm but balanced line under the last word. We might think of this as jointly associative for both climber and poet: the metaphorical horizontal evocation of the joyous release from the vertical ropes and carabiners that stop a climber’s fall; or equally, the poet’s release from language, deliberately letting the line go; the summit having been reached. However, the analogy between mountaineering and writing ends there: the poet displays their roped words, carabinered like woven lace; the mountaineer hauls in their rope erasing all traces of the climb.

A Coda

I too was born in Sheffield, my mother’s hometown, where her side of the family were painters and decorators for nearly a century and my father worked in the steelworks. Whilst Helen grew up in Chesterfield I was brought up ‘down south’ on the borders of Herts and Cambs, where my mother never regained social consciousness, having lost the shopkeeper spirit of camaraderie that sustained her. Seeing life through her eyes, her failed compromise, has given me an exile’s fondness for the town. As such I take to Helen’s writing, and her crafted phrasing, as if it were of the city itself; so I too, like Helen, am channelling identity through another woman’s experience.

Helen Mort’s first collection ‘Division Street’ (Chatto and Windus, 2013) was shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize and the Costa Award and won the Jerwood Aldeburgh Prize. Her second collection ‘No Map Could Show Them’ was shortlisted for the Banff festival’s mountain book awards in Canada. Helen is a Lecturer in Creative Writing at Manchester Metropolitan. In 2017, she was a judge for the International Man Booker Prize.

Birdfall by Adele Myers

Birdfall by Adele Myers

The filmmaker Adele Myers has become recognised in the poetry film world for her spare, sublime and evocative films. She is also something of an exception in the field in that, as a result of teaching DSLR short film production, her films are always honed and crafted in line with the more traditional big budget productions, using film crew, lighting, and sound on set.

Known in the creative world of interactive art and performance in Manchester since the late nineties, she has had over twenty years experience delivering a wide variety of artistic projects and training programmes, including starting Bokeh Yeah! DSLR peer–to–peer training network and production hub. She was working at Manchester College until last year when she left the UK and began teaching local women film in the United Arab Emirates. Look out for Adele’s latest initiative the Timeline Poem-Film Challenge. The challenge is to make a poem film from a selected poem in a certain amount of time.

A chance meeting in 2010 with Ra Page of Comma Press led to her being asked to make her first poetry film. Ra was interested in filmmakers making films based on the poems that Comma Press published. The result was the now highly regarded Racing Time (2012) from the eponymous poem by Chris Woods, capturing the determination and sprightliness of an elderly fell runner as he reached the peak of a climb in freezing conditions.

Selected by Alistair Cook for the Dunbar Filmpoem festival 2013, Alistair then chose Adele as one of the ten filmmakers commissioned to make a film to a poem by the winners and commended poems for The Poetry Society’s annual National Poetry Competition prize in 2013.

The resulting film was Birdfall, based on the commended poem by Danica Ognjenovic. It was premiered at Felix Poetry Festival, and screened at The Southbank Centre, London as well as by Liberated Words at Encounters Short film and Animation Festival, Bristol, 2014.

I spoke to Adele in Fujairah during Ramadan about Birdfall.

S: So, did you choose the poem, because it seemed to gel well with your concise filming style?

A: I asked if we could choose, but we were allocated poems. Initially Danica’s reading wasn’t very clear as it was done on a mobile phone. I asked if actors could deliver the poem but we were asked to work with the original voice, which then needed a lot of editing to make it clearer.

S: Your editing worked well because she sounds very clear. Did you know what she was writing about?

A: No, we didn’t have any contact.

S: I like that, it left it up to you to interpret; you had no preconceptions on the subject. I personally thought she might have been writing about boat people.

A: I thought of that and at one point I looked into the idea of slaves coming over on boats … The poem felt like a vast poem and I didn’t think I could find a lake and boats and birds flying over without a budget, and I thought you could possibility do it in animation but I am more a live action filmmaker and so prefer to work with actors.

Two Films

I don’t know if you know but I made two films. My first idea was about hens and roosters meeting in the Farmyard pub. Bikers come in a pub and the local ‘hens’ have fantasy sex with them, but as the bikers were unaware of this they leave the ‘hens’ disappointed, but they laugh it off as girls might in that situation. I think that possibly confused The Poetry Society. They didn’t want a film that couldn’t be promoted openly on their website to schools. When Danica eventually saw the film she was a little curious as to how I came up with this idea – because it wasn’t how she had envisioned the poem. The second one is more similar to her original ideas.

S: What made you think of that idea? In your other films there normally seems to be some correlation between the poem and the image?

A: It was a domino effect. I couldn’t find a lake; and it was the first line –working out what it meant – ‘We were three hours at sea when the birds began to fall‘. It reminded me of the northern saying ‘three sheets to the wind‘ – meaning being drunk – I thought about if birds were in a situation then drunk; a friend has a country pub in Derbyshire and my northern roots kicked in as I imagined how people might interact in a certain situation. The pub being called the Farmyard was perfect as then the customers became the hens. I imagined the situation of these Rooster birds descending on the deck of this pub and ruffling the feathers of the hens.

Suddenly this Coronation Street goes wild scenario became the narrative. I showed it to Alistair and he was fine, but The Poetry Society was concerned about the sex scenes so I had to make a second film. So I came up with what I thought other people would accept, if I am honest – a Swan Lake scenario –and that would be okay, especially if a ballerina was the bird.

S: Do you know why you chose a confined space?

A: That might have been because it was one of the only spaces we could get on a tight budget that I could also control. I knew someone who ran that space as a studio and so I knew it was available, and I had rehearsed in there and I knew we wouldn’t be disturbed, and we didn’t have time for anywhere else.

S: Pragmatic.

A: It was quite dark. We made the space our own and shot in a day and edited in three days. I made a square box out of cellophane and lit it to create atmosphere. It looked beautiful. Within my films I try and elevate the poems and try and take them somewhere else.

S: What camera did you use?

A: All shot on DSLR. I’ve got a Canon 5D Mark III.

S: The quality of the film is so good.

A: Yes Thanks. All my film so far have been shot on a DSLR. We have strict shooting settings that we don’t go beyond …

S: How many people were involved in making the film?

A: Myself as director, an assistant, a sound editor and of course the dancer Liis-Maria Toomsalu. The main camera – Richard Addlesee followed my directions; I was also second camera on this particular film.

S: That’s a nice place to be; you can watch the other cameraperson and you know how you are covering them. And storyboarding?

A: I often don’t storyboard, especially if I am filming it myself but it helps if there are other crew on the shoot to relay a shot list to them or show an idea, so I have used them.

S: That’s unusual since every other aspect of the filming process is quite tightly controlled.

A: It’s because if I am shooting myself I have the idea in my head. I then go into the editing and know what I want very clearly, better than an editor can interpret, because I was at the shoot, I’ve seen all the footage already as I shot it. Also, usually you’d have a monitor but the way we are doing it we barely look at it, doing a one-day shoot. We also had an assistant to throw feathers at a fan on the floor to make them float. It made the film more abstract, more ambiguous.

S: Did you choose the choreography?

A: I choreographed a bit – because I am from a dance background, I studied Creative Arts at Crewe and Alsager College and majored in Dance. This film also married my dance background so gave me an opportunity to explore dance again. The dancer Liis-Maria is from Eastern Europe, and is classically trained. She was actually my neighbour in Hulme in Manchester, although I’d never knew her before the film.

S: I didn’t know you had been a dancer. Somehow then this film does all seem to make perfect sense, and the symbolism etc., even if you came to it in a roundabout way. What about the make up?

A: The dancer did quite a lot of work on that and her costume – we looked at birds, emblems and tattoos and Swan Lake, and she showed me photos of suggestions. I didn’t make any strict instructions on what she could or couldn’t do; in the end she decided. Liis-Maria is also pierced and tattooed so it was a different take on classical; an alternative classical dance.

S: You chose the music?

A: I originally worked with fairground themes, music box-type sounds, like the ballerina in a box. I wanted something soft to lead you into something but not being sure what it is. I had been going down the fairground route for some time and we rehearsed a lot with that, but in the edit it didn’t work so well.

S: Was it also governed by the softness of her voice?

A: No it was more about the setting – making it mythical and mysterious.

S: What about the budget?

A: After the first poem film I was on a really tight budget. I spent about £400 on this one, including buying the music. I had written to the composers numerous times for permission and I was in Antwerp (about to screen at the Felix Poetry Festival) and waiting for it to go on screen so had to pay 200 euros for the rights just before it aired.

S: Do you always work with someone else’s poem?

A: Yes. And I take a long time choosing the right one. I have never done my own, I might do one day. I write a little poetry, though not all the time, and I’m not sure its any good really, but the other day I thought about sending one to a competition – I thought I quite like that poem.

(extract from interview between Adele Myers and Sarah Tremlett from the forthcoming book on poetry film, published by Intellect Books)

O kas?/ Who?

“O kas?/ Who?” (2012) from AVaspo

Lithuania – Poetry and Place

When I first visited Lithuania in 2009 it was for a British Council funded solo exhibition in Klaipeda. I had a warm and welcoming experience, and was even treated to free accommodation by the gallery. I also travelled alone recording and absorbing life by the Baltic Sea. At that time the country had officially been independent from the Soviet Union since 1990-1991; but of course change is gradual, and political eruptions were (and still are) potentially on the horizon. My exhibition and talk was about Voices and Silences, screening two poetry films and a selection of non-dualist or two-in-one prints, where philosophically and materially both the positive and negative from a printing plate are part of one work. Part of my practice is to create poems and pieces that encourage the viewer to think about this relationship in a contemplative, or paradoxical way.

After six years I feel very fortunate that I can return to Lithuania under the banner of Liberated Words and poetry film. Where better to review the contemporary situation than through the poetic temperature of Lithuanian poets and filmmakers at TARP poetry film festival. One question I want to ask is how much do they think they are changing as a country. Do they aim to include their past in their poetic works as they move forward? A term which has arisen from many older, exiled poets is unbelonging, in a sense adrift from a mother ship that was your home but can no longer be your home. Alternatively, some poets may feel the need to erase the past to begin again; to suppress their national identity for a united philosophical worldview of mankind existing idealistically beyond borders.

The global Internet and the internationalism of poetry film can perhaps transcend the difficulties of other genres, but we have another problem of language and translation. This is an area which has often arisen as English is the dominant language, yet we want to hear the nuances, inflexions and temporal, emotive rhythms of other languages. This is in addition to the translation of words into images that often takes place in poetry film collaborations. So, we have three primary forms of translation to experience and absorb: socio-historic, linguistic and from verbal to visual-verbal.

One poet who can provide us with a glimpse into the poetry film of contemporary Lithuania is Gabriele Labanauskaite – the founder and organiser of TARP poetry film festival. As a poet and dramatist Gabriele began making audiovisual works in 2004 and started AVaspo (Serpent of AudioVisual Poetry) see en.avaspo.lt. She began TARP in 2006 as a logical extension of working in a multimedia environment, with the aim of creating a platform for friends working in different types of poetic artistic expression.

Her work is best described as experimental, performative, music-based poetry film. In some ways she is like the Icelandic singer and musician Björk in that she performs loose narratives which are suffused with the music and visuals; but rather than songs she creates texts which are then interpreted by musicians and video artists. Opposed to the traditional convention of recitation her voice is used like another instrument, as part of a group of highly skilled, avant-garde musicians. The video is then created where she often features dancing to her own rhythms, or moving through strange metaphorical spaces.

In this film O kas? or Who? from 2012 Gabriele and friends go on a car journey to a picnic. Whilst in some senses surreal in approach we have a strong sense of her national identity. The sense of a looming presence and the words ‘Who is behind this brick wall’ are repeated; and ‘they’ are always felt to be present even amongst nature. It is important to remember that her work, featuring women, makes the difficult environment she has grown up in all the more poignant. The innocent act of a picnic juxtaposes with an insistent soundtrack, and whilst animated flowers twirl across the screen joyously, encroaching leaves twine around the girls and pull them away. Finally they dance in abandonment as the music reaches a crescendo. This is a film which, strong on visual and musical content, needs very little translation; it is a new tale of a new Lithuania finding its feet, told from a woman’s perspective.

Gabriele will be one of the poetry filmmakers featured in my book on poetry film which will be published by Intellect Books.

Sarah